Why Does All of This Ultimately End in Indifference?

Indifference: From Not Distinguishing to Not Involving Oneself

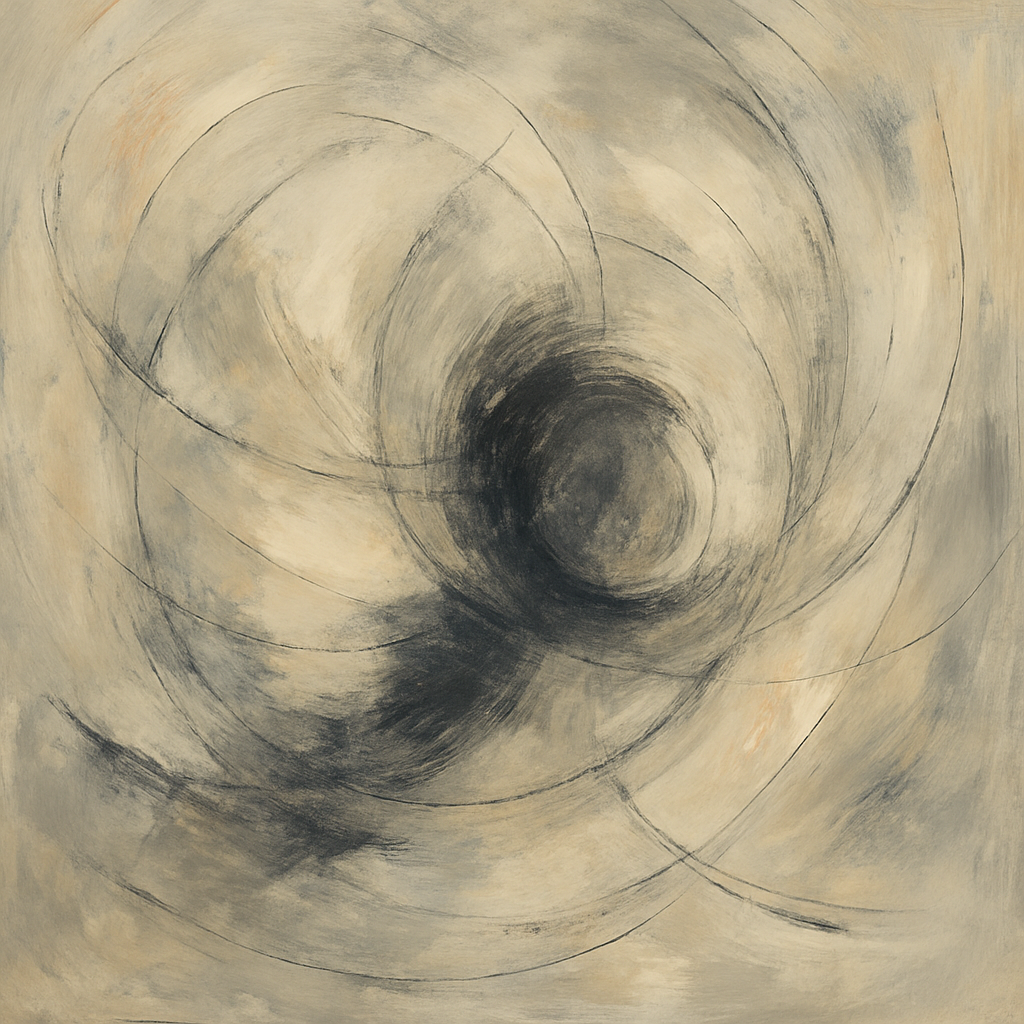

“This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper.”

— T. S. Eliot, The Hollow Men (1925)

The word indifference comes from the Latin in-differentia, which literally means “no difference”: what is not distinguished, what does not matter, what is all the same. Originally, it carried no ethical weight. In medieval scholasticism, it was used to designate morally neutral acts, with neither inherent goodness nor evil. It was a logical category, a way to describe that which required neither judgment nor decision. The indifferent did not imply action or omission, only the absence of the need to choose.

Over time, this neutrality shifted toward the realm of affectivity, and from there, toward responsibility. The indifferent stopped being that which did not require action and became the gesture of someone who chooses not to respond, not to get involved, even when something calls for presence. It became a form of omission that, although passive in appearance, began to have real consequences. What was not done, what was let go, began to weigh.

It was in the twentieth century that this change became unavoidable. The political and moral catastrophes of the time—the concentration camps, the atomic bombings, forced exiles, genocides, dictatorships—radically transformed perceptions of passivity. Between the First and Second World Wars, it is estimated that more than 80 million people died. That scale of destruction, together with unprecedented visibility of human suffering—through the press, photography, and later film—forced an ethical reevaluation: not acting, not speaking, not taking sides ceased to be a neutral gesture. In many cases, it became a way of sustaining by silence what others enacted through violence.

Since then, indifference has carried that legacy. As Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor, wrote: “The opposite of love is not hate, but indifference.” The phrase rests not on the psychology of emotions, but on an ethics of relationship. The true abyss lies not in conflict, but in the ability to look without seeing, know without intervening, hear without responding.

Postwar times did not just reshape the century’s political map: they also modified the ethical weight of certain words. In a context of social reconstruction, expansion of rights, and consolidation of the Welfare State, concepts like “commitment,” “solidarity,” or “collective responsibility” became central, while indifference came to be seen as an unacceptable form of abandonment. It was no longer an attitude of distance: it was a symptom of moral disconnection, the failure of human connection.

That historical moment, which articulated a new pact between individual and community, between memory and politics, turned indifference into a structural problem. It is not simply about inaction, but about recognizing that what is omitted also shapes the world.

Indifference as a Form of Emotional Balance

After World War II, indifference was inscribed into moral consciousness as an ethically unacceptable gesture. This sense persisted for some time, sustained by the discourse of collective responsibility. Involvement remained a value: not as heroism, but as the minimum form of belonging.

But with the neoliberal turn and the gradual individualization of lifestyles, that principle began to lose force. The committed subject was displaced by the individual who owes everything, above all, to themselves. The ethics of connection ceded ground to the logic of the self as project. In this context, indifference was no longer a sign of disconnection but a symptom of maturity. Not getting involved, not exposing oneself, not carrying others’ burdens began to be presented as self-care, balance, or emotional intelligence.

In contemporary culture, centered on the individual as a self-regulating system, indifference appears disguised as prudence. It’s common to hear phrases like: “I don’t have time for that,” “I have to take care of myself,” “I need to prioritize myself.” Connections with others are seen as threats to inner balance, as unnecessary burdens or distractions from personal goals. The mandate is clear: look out for yourself. Everything that does not directly contribute to personal wellbeing—or its digital display—becomes expendable.

This withdrawal is not only a defense: it is a socially celebrated model. Sustained commitment to others’ suffering does not fit the ideal of efficiency, performance, and shielded wellbeing. In a world where time is monetized, emotion is regulated, and bonds are managed, involvement becomes a miscalculation.

The contemporary self has made abstention a virtue. Not responding, not taking a stand, not supporting is seen as maturity. This self, which sees itself as fully autonomous, has become adept at deactivating others’ demands. It sees, but does not respond. It understands, but does not allow itself to be affected. It recognizes, but is not interrupted. It is not about coldness, but emotional efficiency: maximizing resources, regulating exposure, avoiding conflict.

In this way, a shielded, regulated self is built, consistent with its own manual of emotional efficiency. A self that neither hates nor rejects, yet does not allow itself to be penetrated. It does not intervene, does not move, does not respond. It repeats its own gestures, confirms its values, amplifies its judgments.

A self so careful about exposure that it ends up not getting involved in anything. The perfect subject of the present: self-sufficient, contained, impermeable.

Indifference as Denial of Difference

There is another, more structural form of indifference, directly related to its original etymology: not distinguishing the different. This form does not reject, abandon, or directly attack. It simply does not see. It does not see the other as other. It absorbs, translates, or interprets the other according to its own frameworks. It is the logic of someone who does not listen because they already believe they know what the other will say. Of someone who dismisses others’ suffering because it does not resemble their own. Thus, the most common reaction to difference is not outright rejection but simplification, neutralization.

One of the most common forms of indifference is pathologization. It is not an insult, nor a direct exclusion, but a displacement of difference to a terrain where it loses legitimacy. What could be an ethical stance, a different way to feel or act, is interpreted as dysfunction, as a disorder, as a clinical pathology. Thus, sensitivity is seen as weakness, devotion as insecurity, persistence as obsessive disorder. The different gesture is diagnosed and its value is nullified.

Another widespread form is caricature and mockery, which consists of reducing what is uncomfortable to a funny exaggeration, a harmless excess. The content of the difference is not debated; it is neutralized through distortion. The gesture becomes oddity, anecdote, ridicule. This form requires no argument or open disagreement: it is enough to deprive it of meaning, to make it a caricature. There is no confrontation, but neither is there recognition. Mockery is not always direct: sometimes it lies in the tone, in omission, in the laughter that turns conflict into anecdote. Humor, in this case, functions as a way to manage affect related to what one does not wish to process.

Another subtle form of indifference is assigning your own motives to others, as if there could be no desire, commitment, or ethical gesture outside your own system of meaning. Here, there is neither mockery nor diagnosis, but something more insidious: an anticipatory understanding. What the other does or says is understood through pre-formulated frameworks, which allow one to maintain stability in one’s point of view. This is not indifference from absence but from imposition. Not seeing the other because one already thinks they know what lies behind. This form of indifference does not deny the other, but replaces them with a domesticated version.

Conditional tolerance appears as yet another form of indifference: when difference is admitted only under certain conditions. It is accepted as long as it is not a bother, does not alter, does not destabilize the emotional climate or the self’s comfort. The other can be present, but not active. It is granted a limited, regulated, decorative place. There is no exclusion, but also no real openness. Hospitality becomes a gesture of control. Something is allowed to be expressed, but only if it does not demand a structural transformation of how we relate, organize, or think.

Silencing, in turn, is the most radical form of this logic. The difference is not pathologized, not ridiculed, not tolerated conditionally: it is simply omitted. There is no response, no acknowledgment, no echo. The conversation continues as if nothing happened. The gesture is not attacked, but pushed to the margins. This form of indifference requires neither confrontation nor justification: it is imposed by its absence. There is no scandal, no confrontation, but also no connection.

And this very process is reproduced on a global scale. Indifference becomes the perceptual structure of the world. Violence is accepted if it is distant, corruption if it is stable, injustice if it does not disrupt routine. Destruction is rationalized as strategy, poverty as accident, war as necessity. The geopolitics of indifference is not denialist. There is no need to lie: merely using the correct names is enough. The aggressor becomes the “dominant actor,” war is “strategic intervention,” hunger is “food crisis,” and occupation is “international presence.”

Within this framework, recognizing the other as truly other—as irreducible, as non-instrumental, as overflowing—is useless, even dangerous. It may demand our involvement, a shift in stance, redistribution of time or affection. Therefore, the most efficient way to resolve the presence of the other is not to distinguish it: to reduce it to what is familiar, project our motivations onto it, make it a variation of the same.

To truly recognize another means accepting we will never fully understand them. That they do not fit our categories. That they might have reasons, pains, pleasures, and timelines foreign to us.

But we live in a culture that rewards what can be explained quickly, what feels good, what reaffirms the self. Difference is cognitively costly, emotionally risky, and socially uncomfortable. Thus, even without hating it, we nullify it.

And it is in this nullification that indifference becomes final. Not because we withdraw from the world, but because we remain in it without being touched by anything. The world does not end from too much noise. It ends from too little disruption. From a well-modulated silence that does not scream, does not argue, does not question.

We are not facing an explosion, but a sustained erosion. A world that falls apart without raising its voice is not a world at peace: it is an anesthetized world. Indifference is not a lack of information. It is an excess of interpretation from the self. It is the inability to recognize what the other does without translating it.

To distinguish again, to get involved again, is not a heroic or epic task. It is merely the radical gesture of not letting everything dissolve while we look the other way.